Warren County PCB Saga

The Warren County protests started the environmental justice movement in this country. Numerous journalists and photographers covered the protest, but few did so on a regular basis. Only one created a body of work that captured this seminal moment in the development of a major social and cultural force.

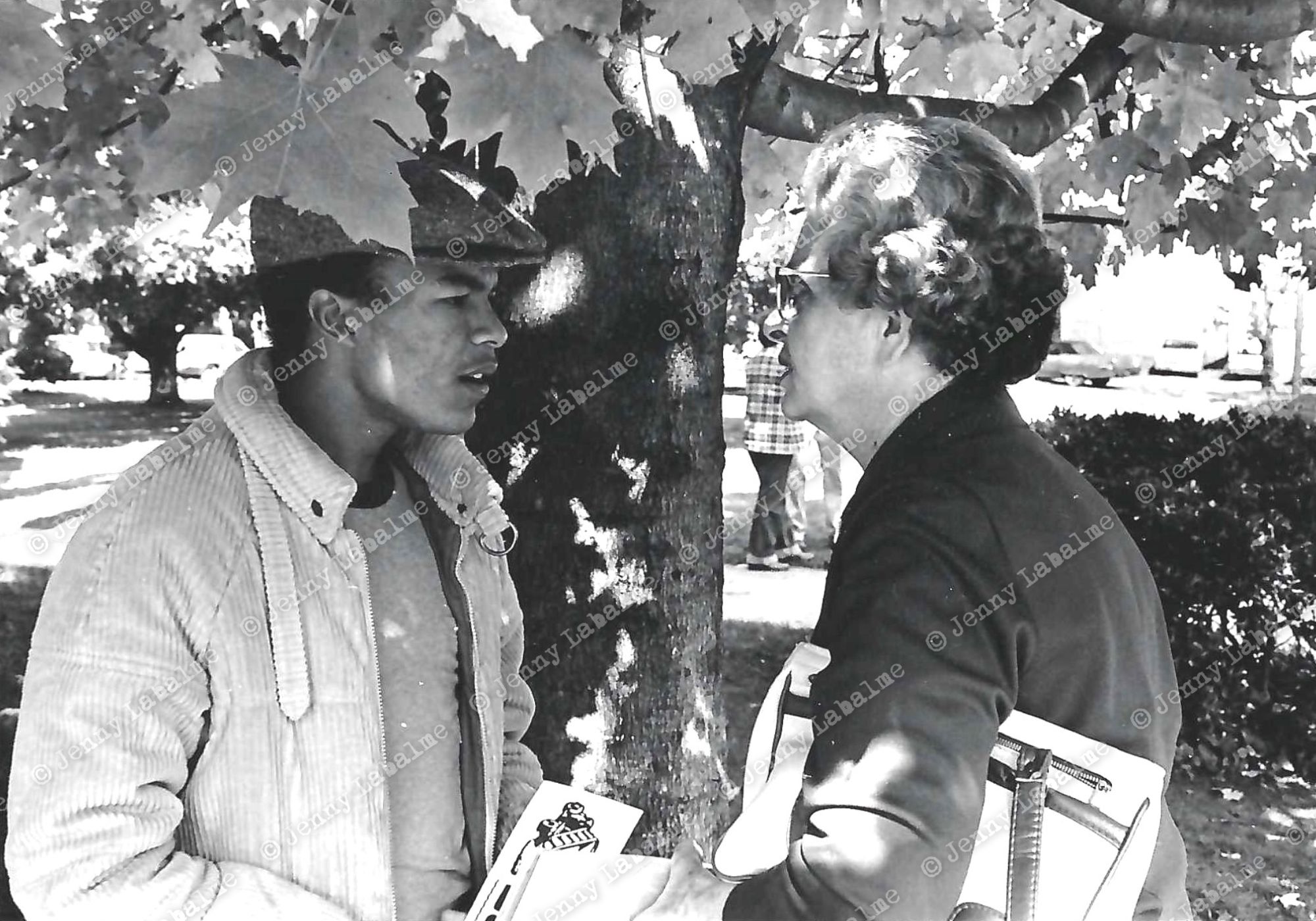

Jenny Labalme was in Warren County, North Carolina with a standard Pentax camera and a generic telephoto lens during the 1982 PCB demonstrations. At the time, she was a self-taught photographer and recorded the protests for a documentary class at Duke University, where she was a full-time student. She continued to make trips and followed the Warren County story several years after the protests.

Shortly after graduating from college, Jenny published her photos in a small book called A Road to Walk. This website is an effort to make Jenny’s copyrighted photos and coverage more widely available.

A Toxic Threat

In 1978, the state of North Carolina discovered the illegal disposal of 31,000 gallons of PCB (polychlorinated biphenyl) transformer fluid along 240 miles of roadways scattered across 14 counties. Some levels of PCB, a known carcinogen, were 200 times above the contamination level set at the time by the Environmental Protection Agency.

At the end of that year, the state chose Warren County for a PCB-landfill site. Warren Country residents argued their county was targeted because it was 64 percent Black, the highest percentage of any county in the state.

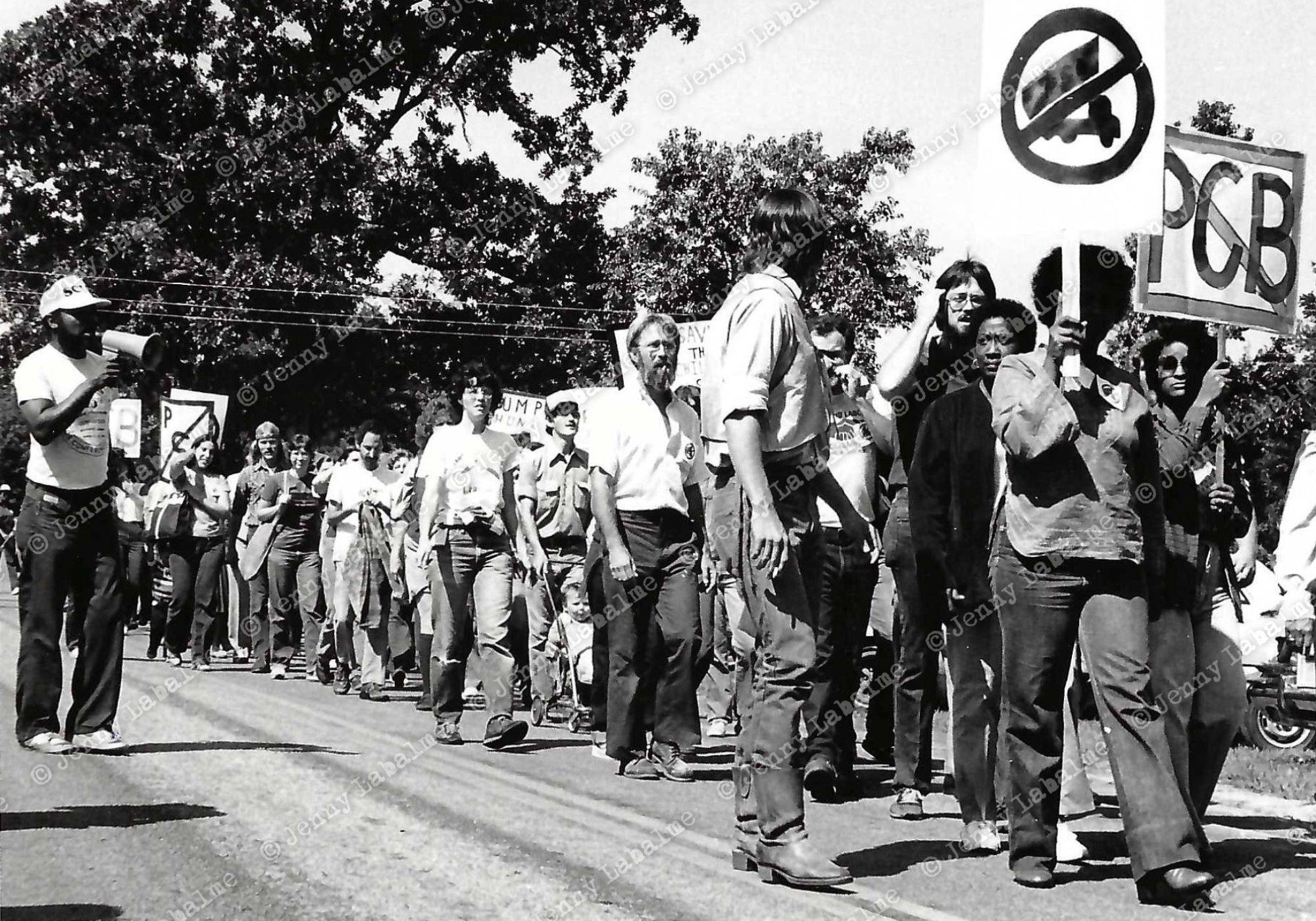

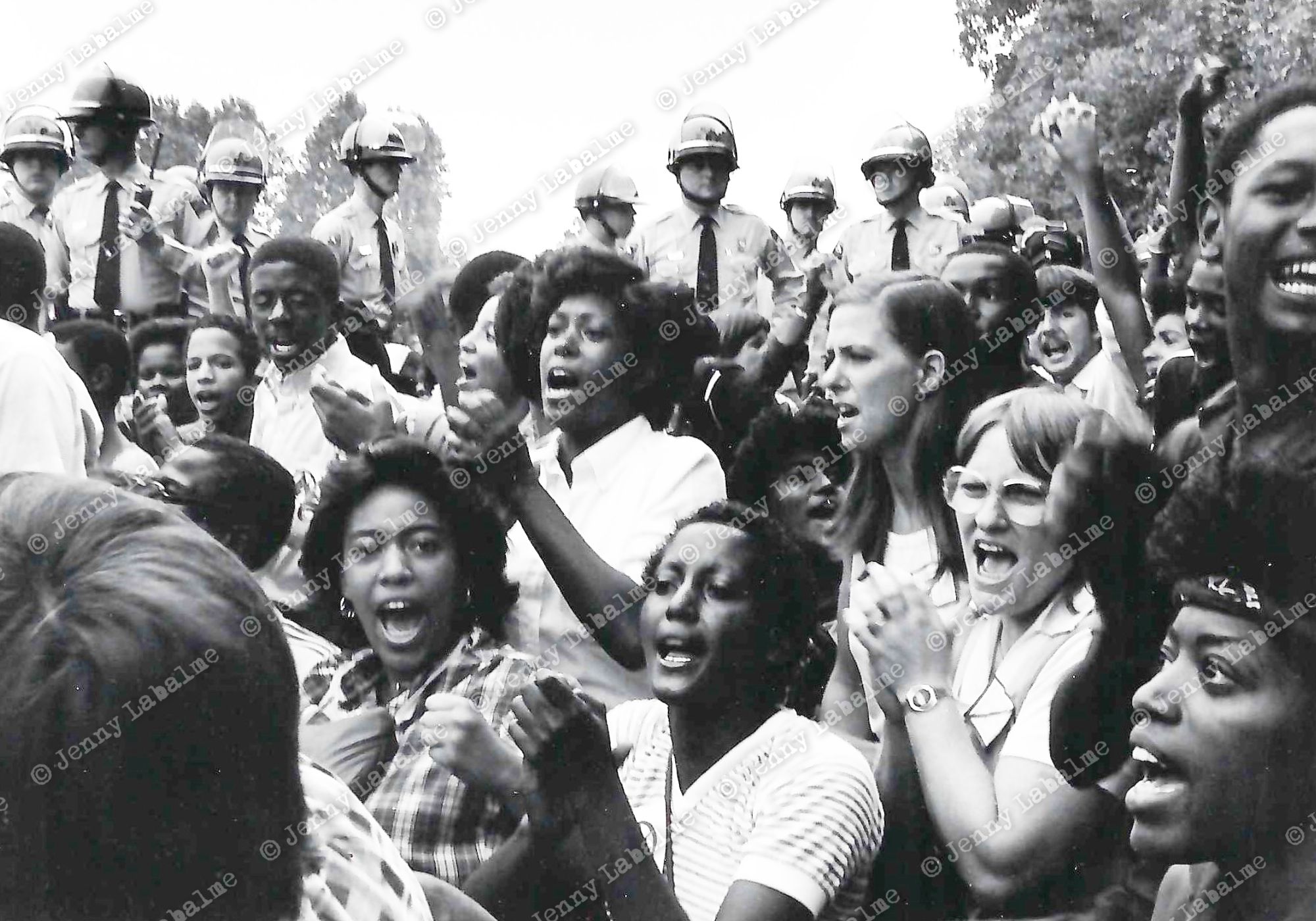

Numerous lawsuits failed to stop the state’s plans. In September 1982, as a last resort, the community turned to protest and civil disobedience with a lot of ire aimed at North Carolina Gov. James B. Hunt. It was the first time nationwide that anyone was arrested and jailed for protesting dump trucks hauling toxic-laced dirt.

Six weeks of peaceful demonstrations and more than 500 arrests didn’t halt the landfill. However, a voter-registration drive succeeded in getting the first Black majority on the Warren County Commission and Blacks into several other elected positions in November 1982. Subsequent studies pointed to a clear link between hazardous waste site locations and the surrounding racial makeup, leading the Rev. Ben Chavis to create the term “environmental racism.” Repeated citizen efforts prompted the state to detoxify the landfill, a process that took five years and was completed in 2003.

The 1982 protests are now referred to as the “birthplace of the environmental justice movement.”

In September 2022 — and 40 years after the protests — Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Michael Regan announced in Warren County that $3 billion will be distributed nationwide to underserved communities affected by pollution and that it would be administered by a new Office of Environmental Justice and External Civil Rights.

A Warren County PCB Protest Song

to “Come by Here My Lord” (Kum-by-ah)

(Crafted by Deborah Ferruccio)

Well, Warren County has some PCBs;

They’re from the governor; he does what he please.

But we will dump Jim Hunt before too long.

Oh Lord, come along.

We’ve got a road to walk; it’s mighty steep too.

But one thing that we know is true,

Let history not be repeated,

A people united will never be defeated.

The way we’re walking is dark and long,

But while we’re marching we’ll sing our song.

Give us faith, Lord, when we can’t see.

Oh, Lord, come by me.

Our good old earth we’ve got to guard and share;

We’ve got to keep her safe and free from care,

And that means standing up for what is right.

We’ll fight the poison with all our might.

We won’t stop, oh Lord, we’ll barely rest.

We’re committed ‘cause the truth is our test.

We have righteousness on our side;

Those poison devils had better hide.

Some folks think we’ll never win,

That toxic waste is a deadly sin,

But we ain’t gonna let nobody turn us around.

We once were lost, but now we’re found.

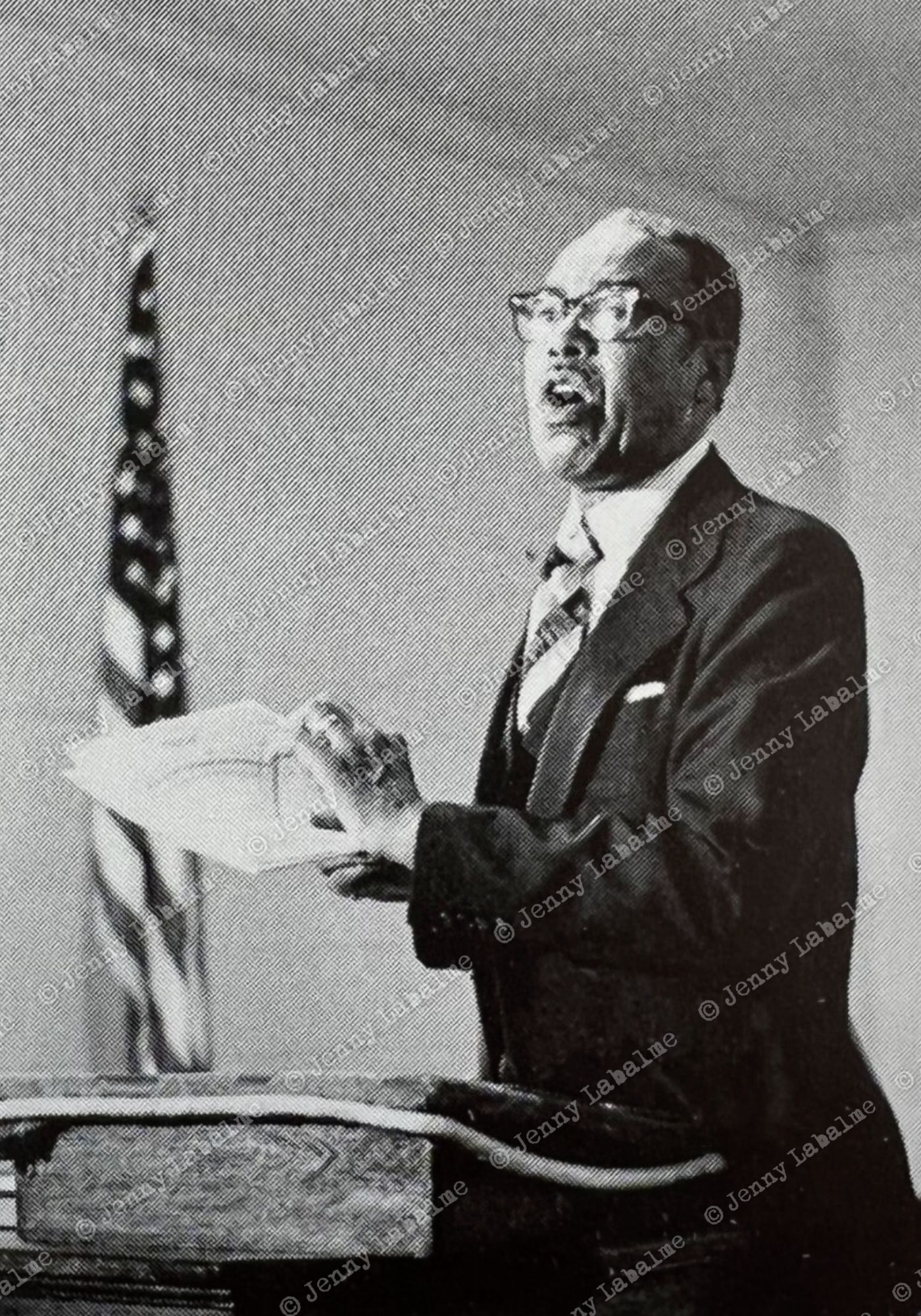

The Rev. Luther G. Brown, pastor of Coley Springs Baptist Church

A Wave of Support

Coley Springs Baptist Church, located two miles from the landfill, became the gathering and rallying spot before each protest. Local church leaders and the Warren County Citizens Concerned About PCB played an integral role. Few residents knew how to demonstrate. So, the Coley Springs pastor, the Rev. Luther G. Brown reached out to ministers he knew such as the Rev. Leon White, field director of the United Church of Christ’s Commission for Racial Justice in Raleigh, North Carolina.

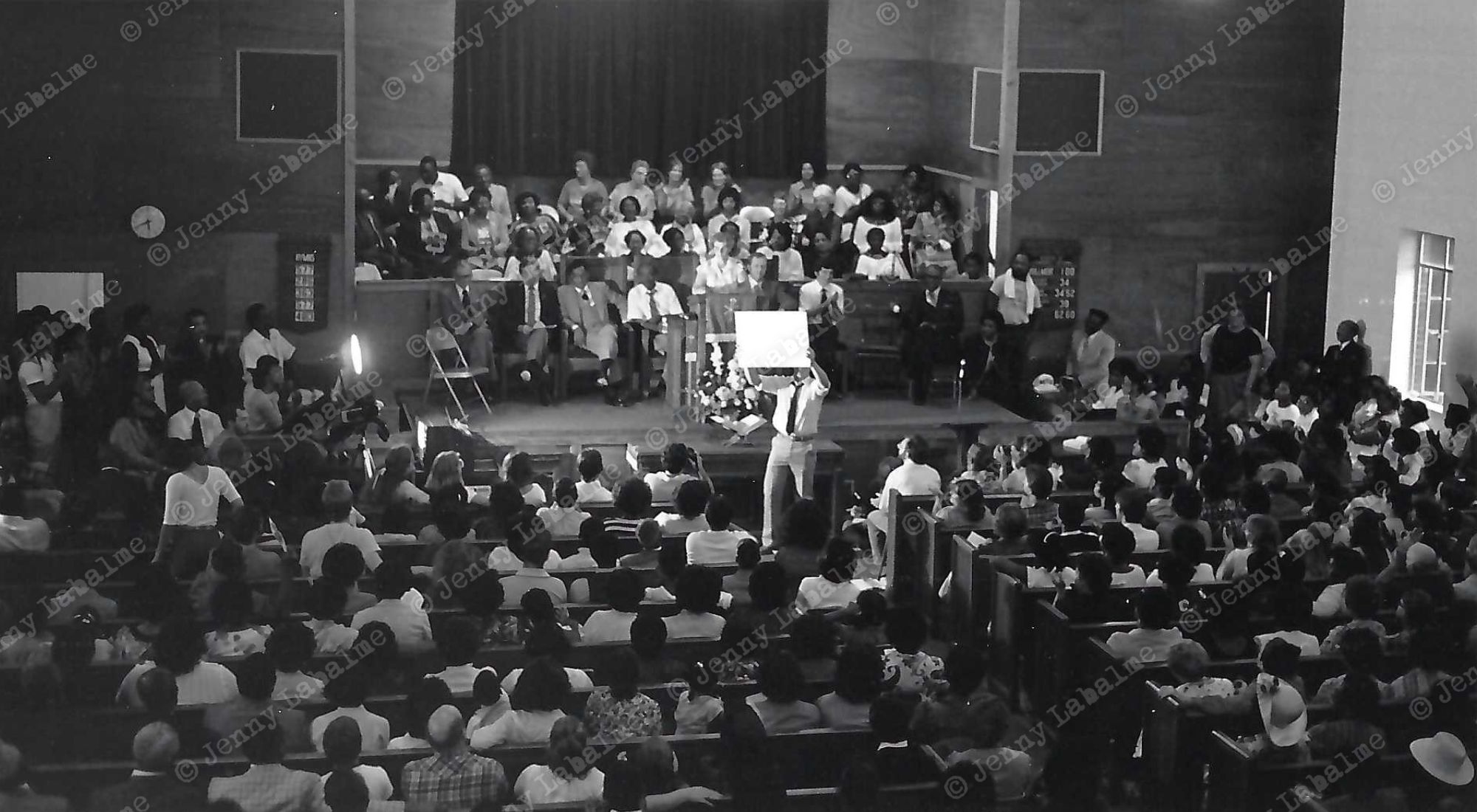

During the protests, people packed the church’s pews. They prayed. They sang. They chanted anti-PCB slogans. Memories from the 1960s civil rights movement were nearby on the church’s paper fans adorned with watercolor portraits of the Rev. Martin Luther King, John F. Kennedy and Bobby Kennedy.

“You are not going to have a Black movement in the South without including Black Christians — no way, no way. That is the basis of it. You always have to involve the church and have it be the gathering machine”

The Rev. Leon White, field director of the United Church of Christ’s Commission for Racial Justice in Raleigh, N.C.

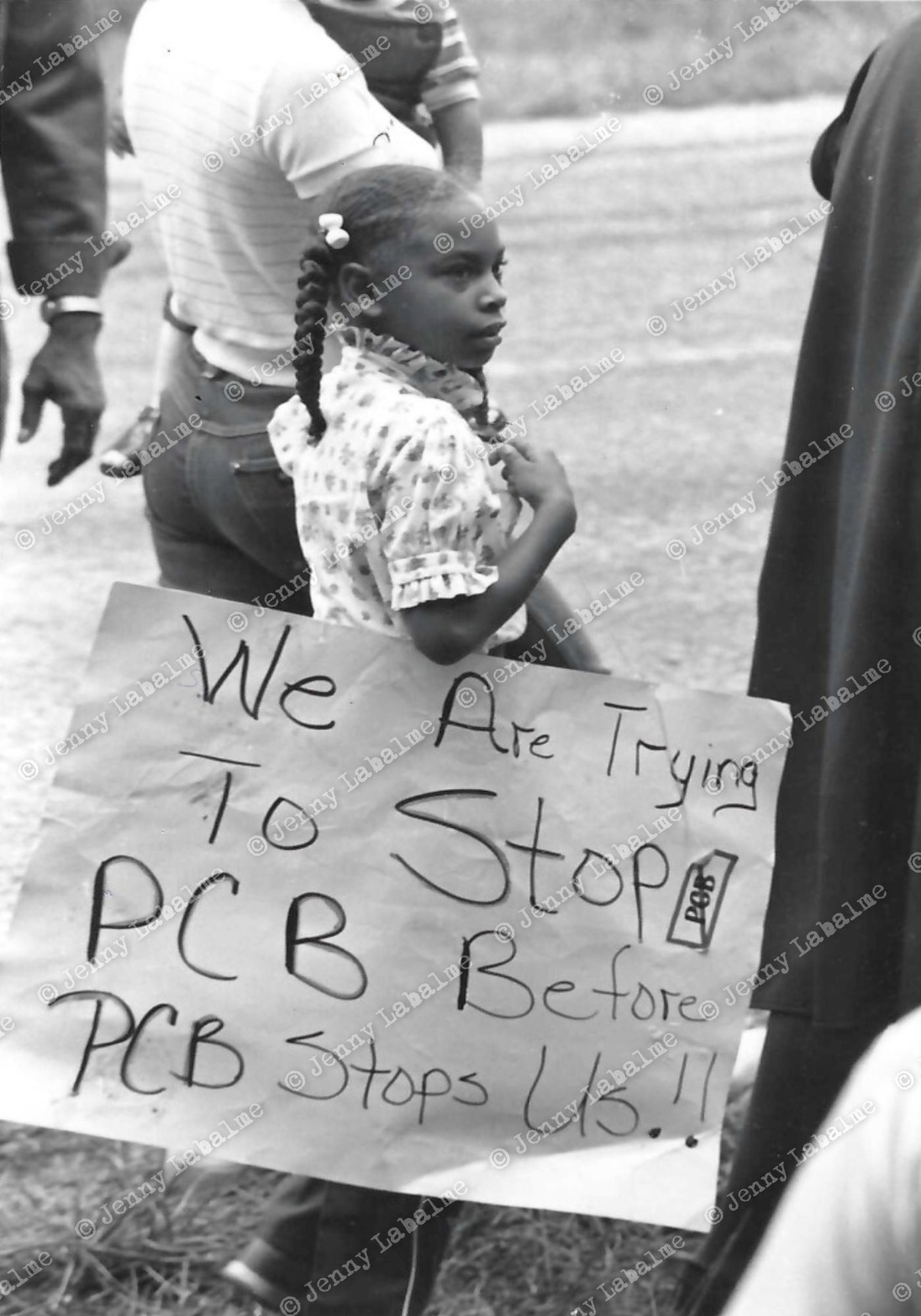

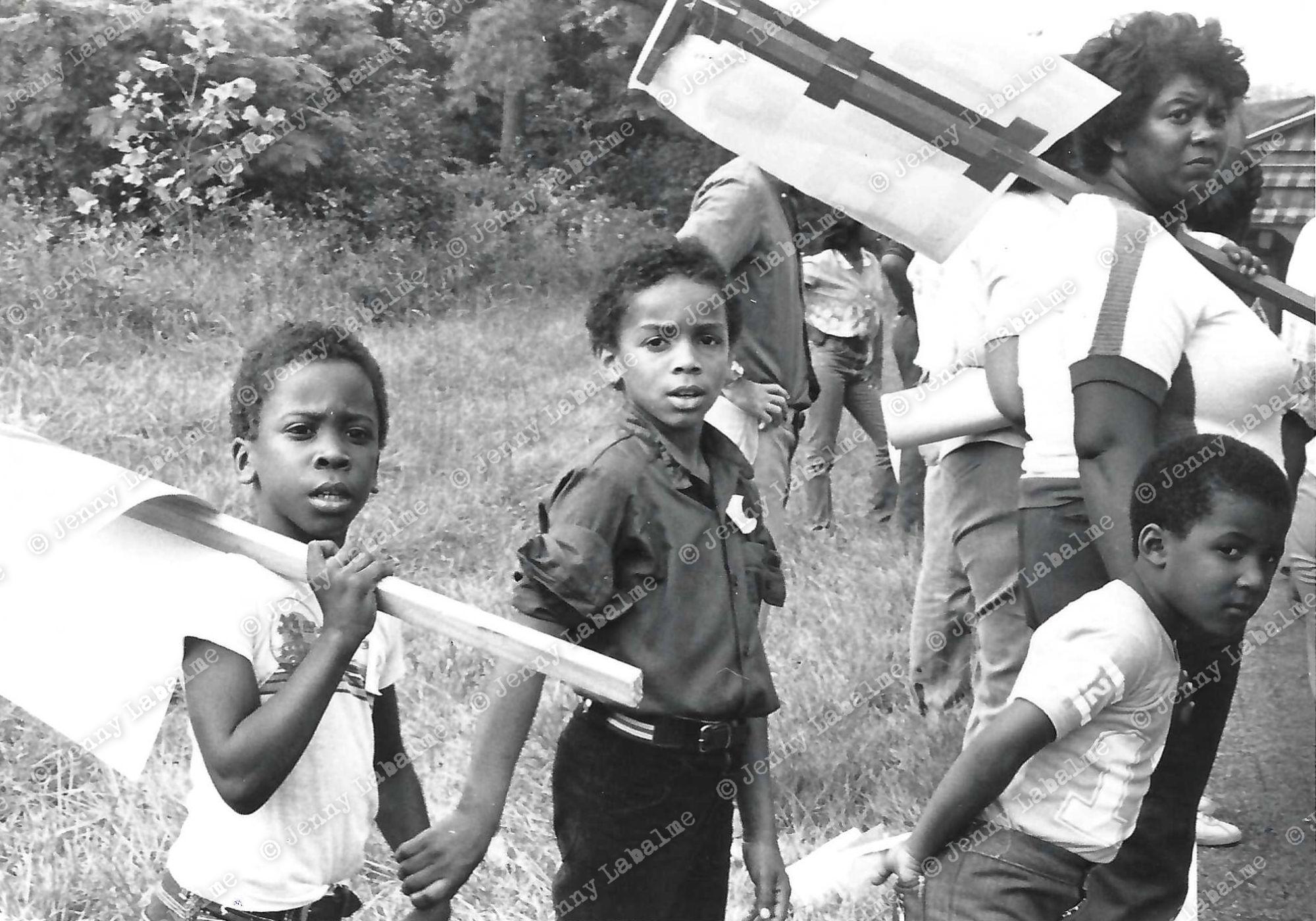

After meeting in the church, marchers often left chanting: “The people united will never be defeated.” Demonstrators were multiracial. They sported paper anti-PCB “buttons,” carried homemade signs and sang protest songs as they walked to the landfill.

“We don’t want no PCB, give

it to Hunt don’t give it to me.”

Race and Politics

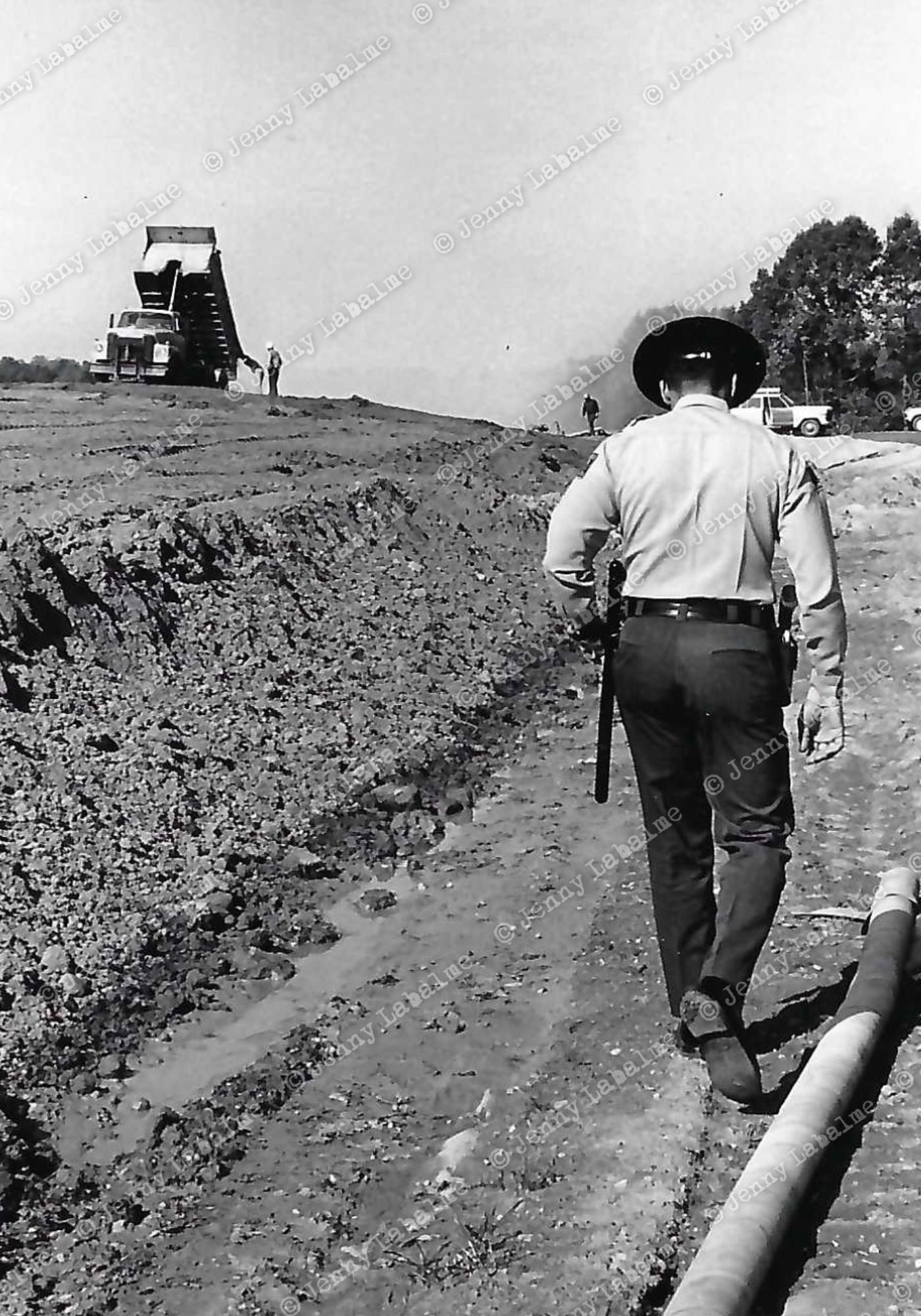

It took roughly six weeks for N.C. Department of Transportation trucks to rumble in and dump their loads.

“It’s an environmental issue as well as a human rights issue because you’re discriminating against a community by threatening it with a toxic chemical,” said Ken Ferruccio, president of the Warren County Citizens Concerned About PCB.

Shocco Township, the site of the landfill, was 75 percent Black and lacked elected representatives. Out of 100 North Carolina counties, Warren County ranked 97th in per capita income.

“It’s one thing to be poor,” said local resident Henry Rooker. “It’s another to be poor and poisoned.”

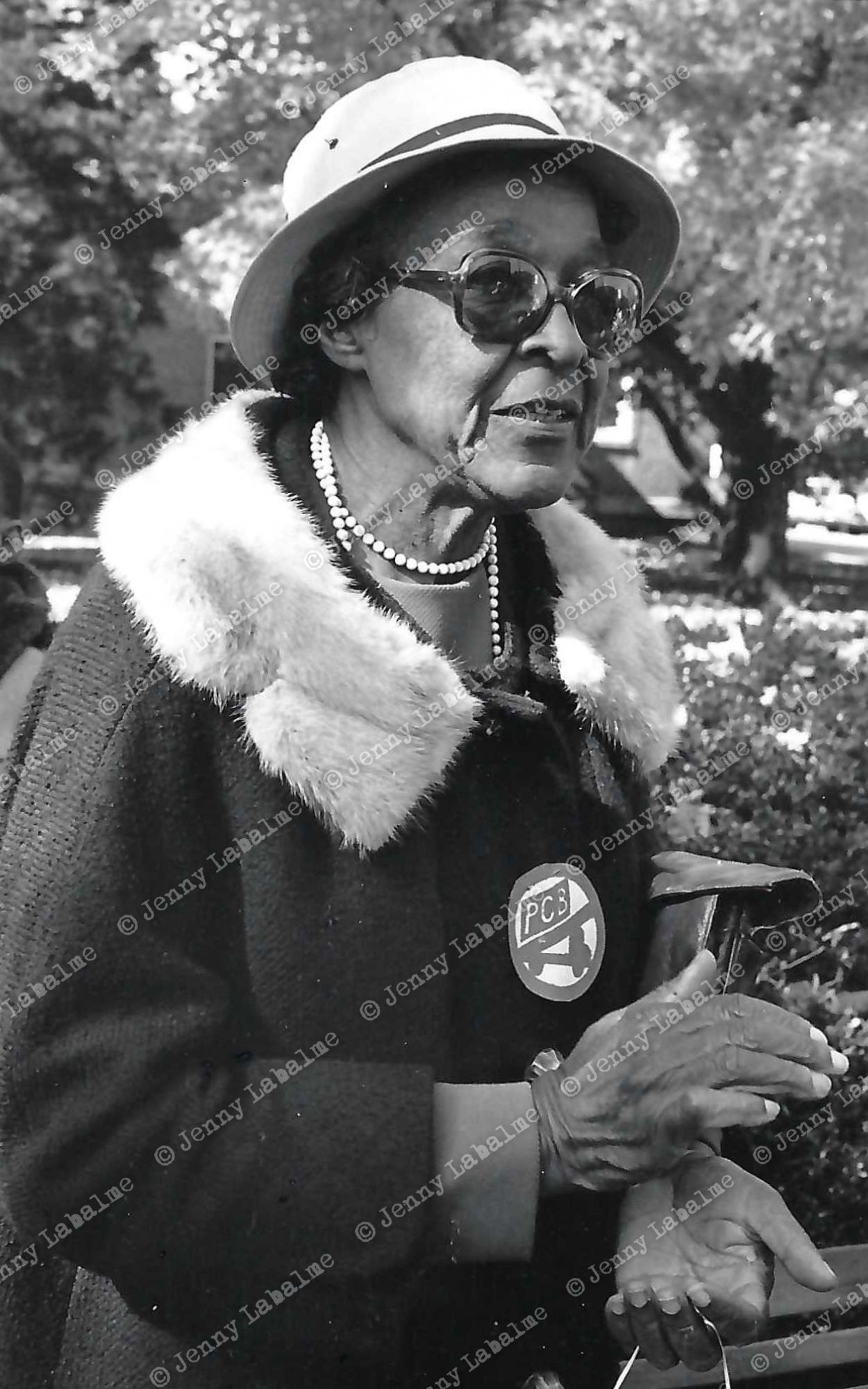

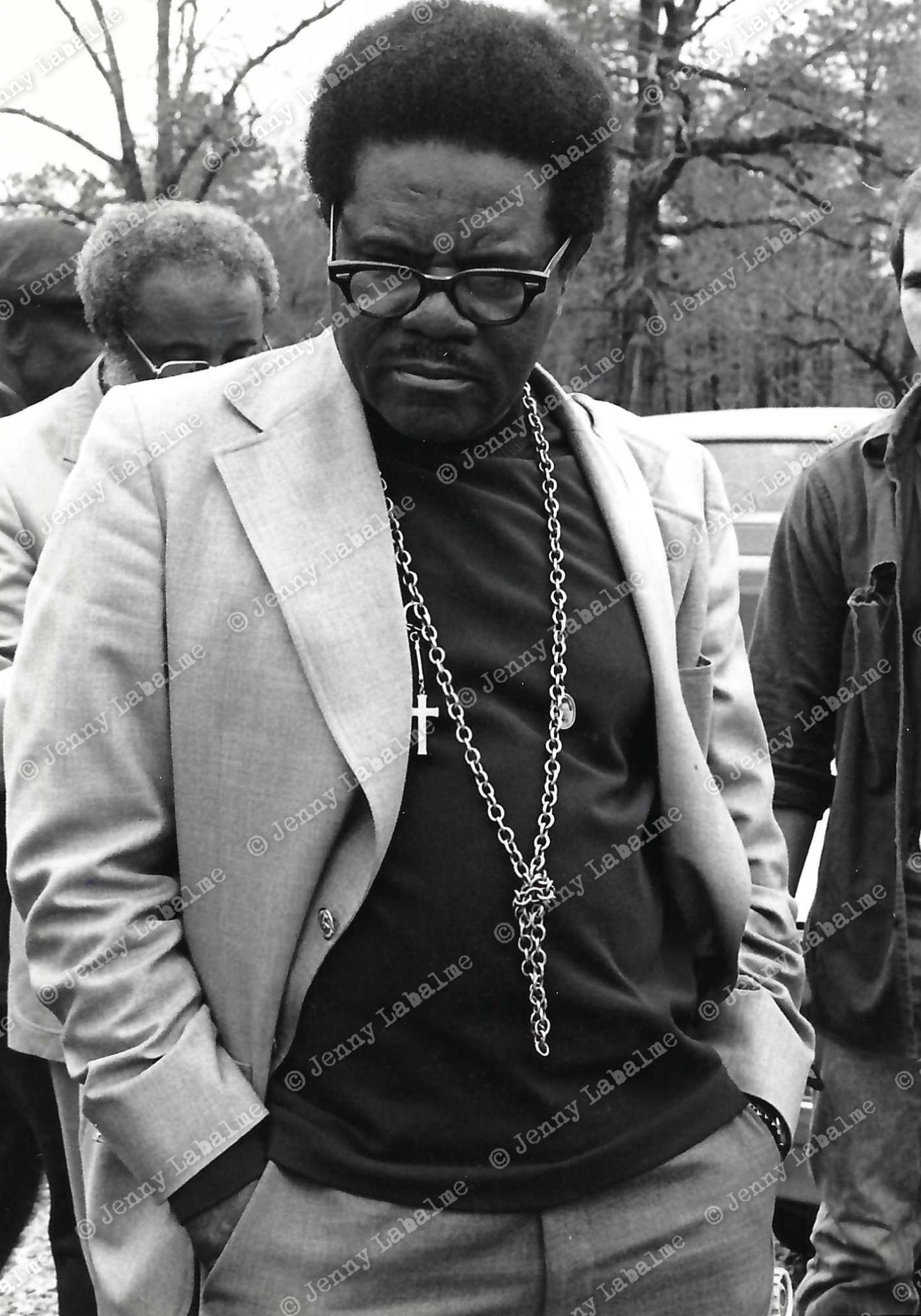

The Rev. Ben Chavis, deputy director of the United Church of Christ’s Commission for Racial Justice

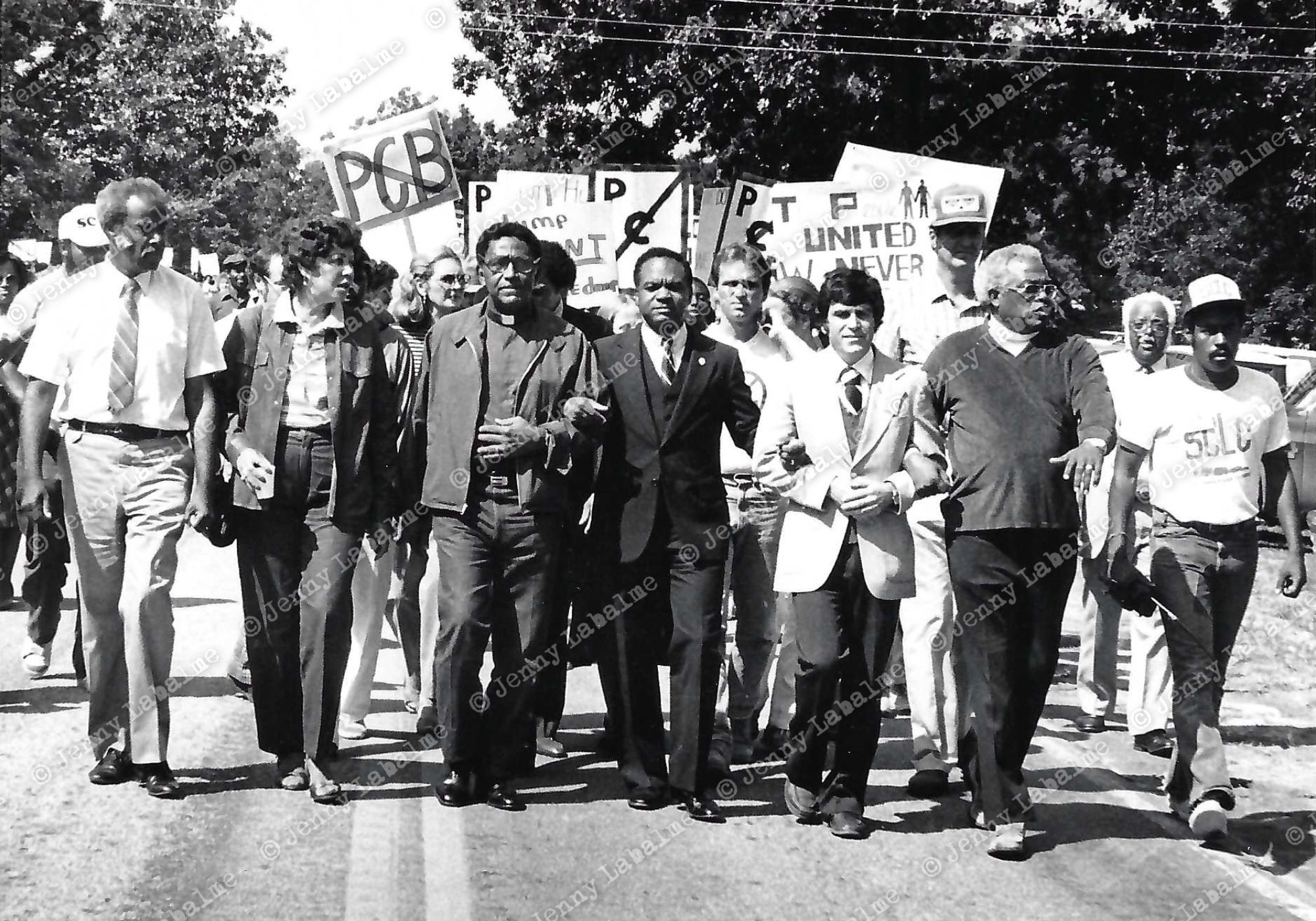

The Rev. Leon White; Evelyn Lowery; Dr. Joseph Lowery, Walter Fauntroy, Ken Ferruccio, Rev. Curtis W. Harris and Dr. James Green lead a march on Sept. 27, 1982.

“Black and white together, ain’t no stopping us now.”

Social Justice

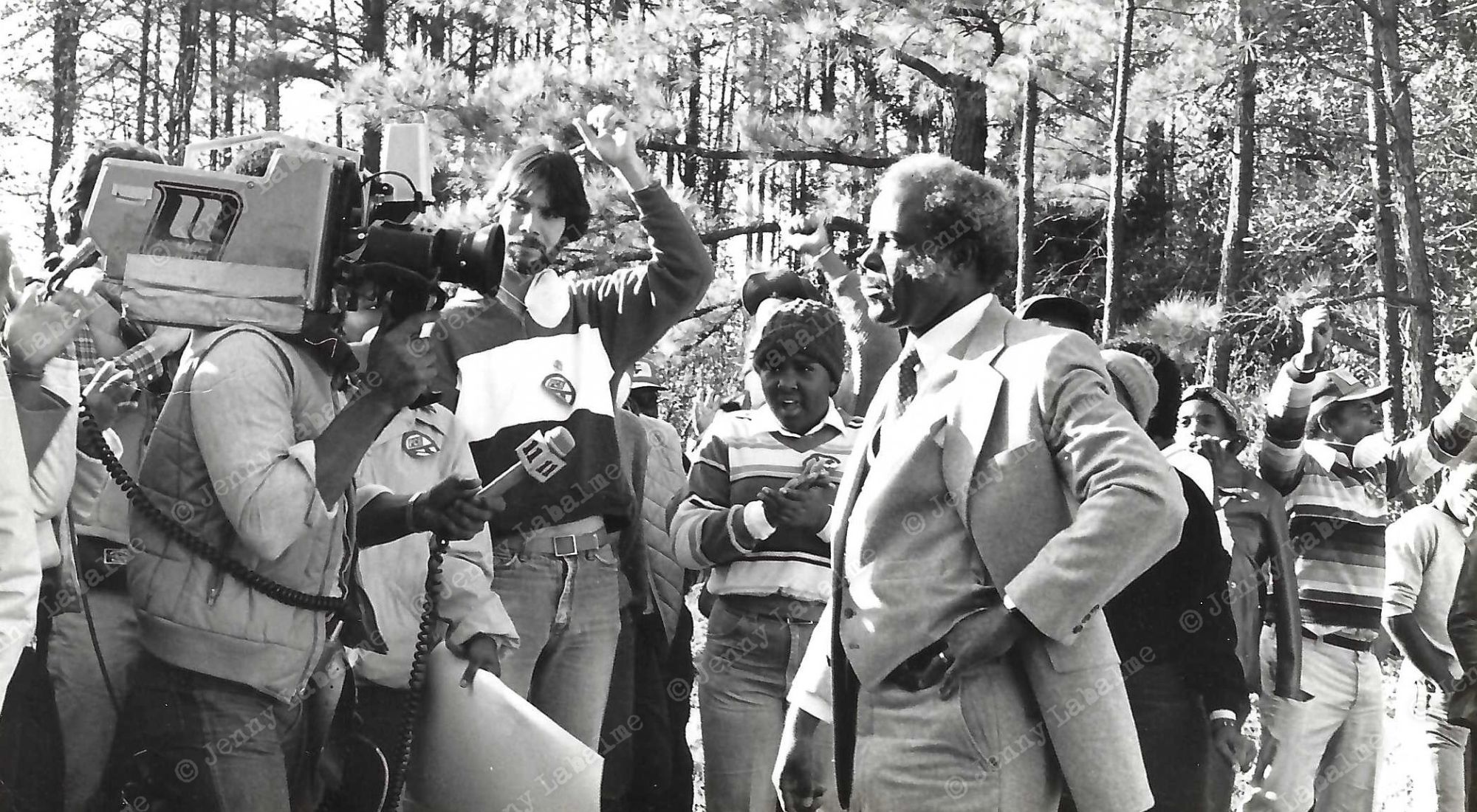

Several environmental and Black civil rights leaders helped bring national attention to the protests.

They pointed out that environmental and racial issues were linked to human and civil rights issues.

Among those who appeared were Lois Gibbs, a leader in the Love Canal fight in upstate New York and former Environmental Protection Agency policy analyst William Sanjour, who spent years revealing how EPA actions endangered public health.

Black church leaders with ties to civil rights groups coupled with their community organizing skills played an instrumental role.

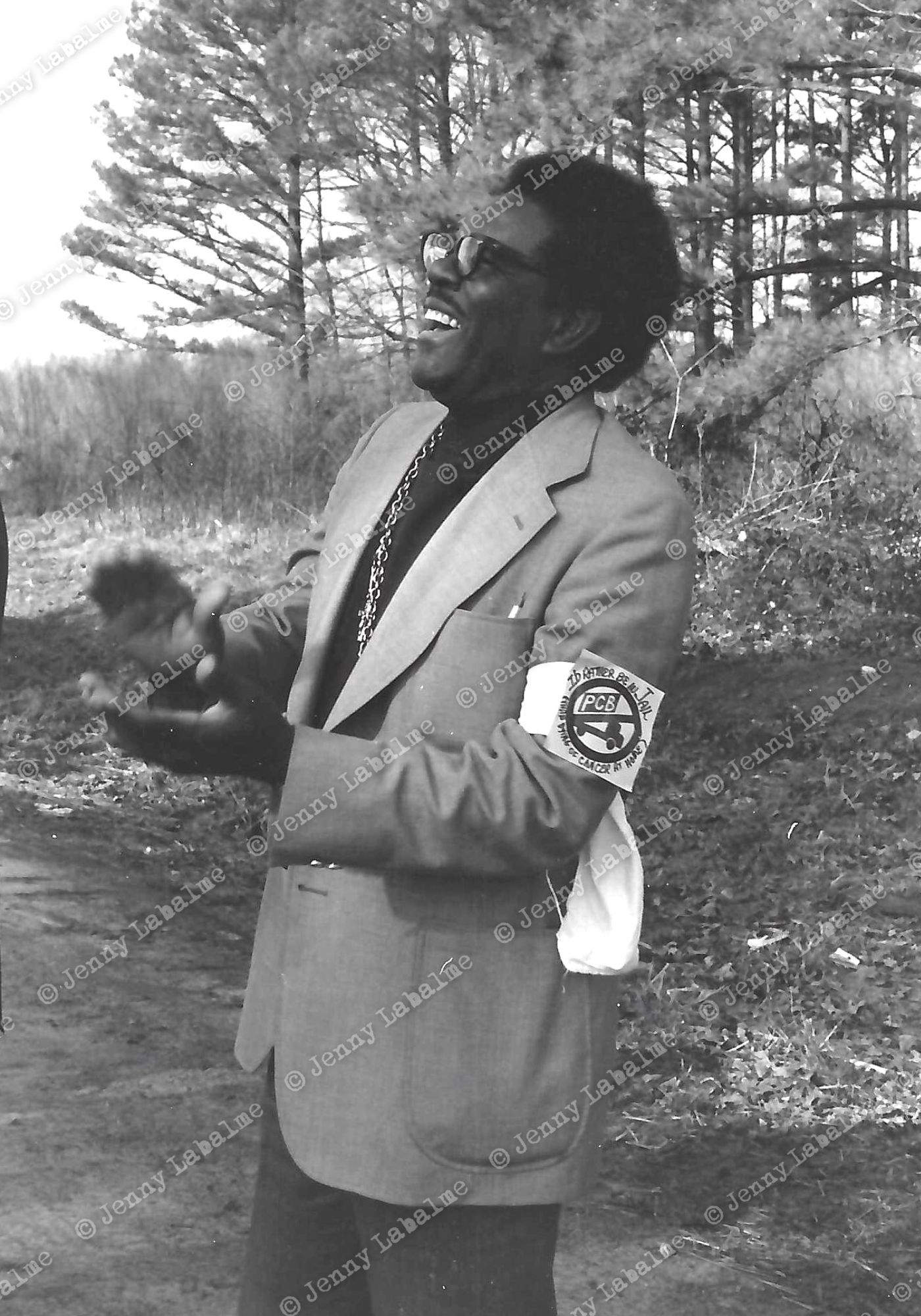

They included: The Rev. Ben Chavis, deputy director of the United Church of Christ’s Commission for Racial Justice; Dr. Joseph Lowery, president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference; Walter Fauntroy, the District of Columbia’s congressional delegate; Floyd McKissick, a Durham attorney and former president of the Congress of Racial Equality; and Golden Frinks, a North Carolina native who had experience from the civil rights movement.

“All these politicians tell us Warren County was not chosen because it is Black and poor. That is the biggest lie that has ever been perpetrated on the people of North Carolina.”

North Carolina native and civil rights veteran Golden Frinks had a charismatic presence. He was a fixture at almost every march and meeting surrounding the protest. With his commanding baritone voice, he led many of the protest songs.

Click to listen to song

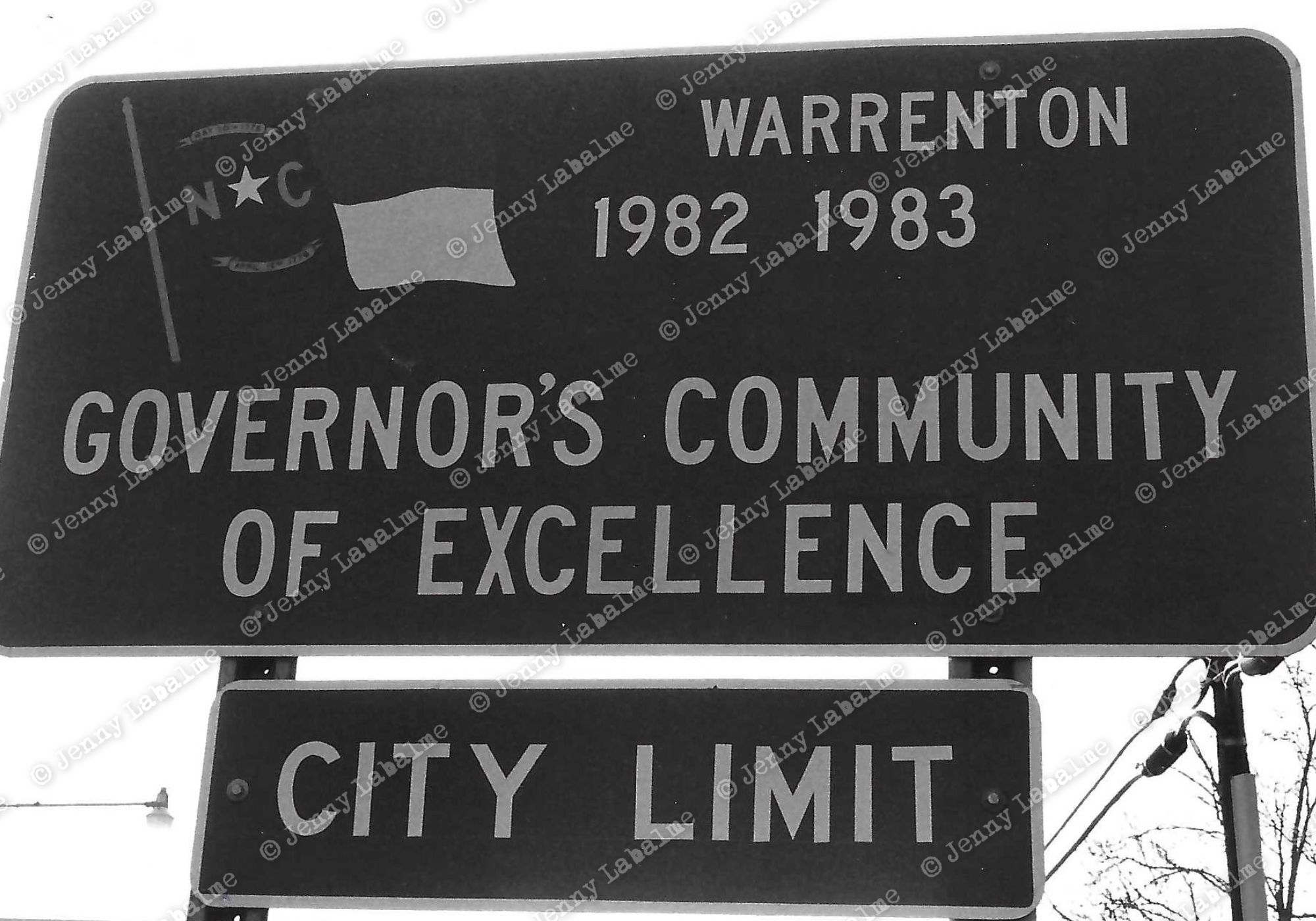

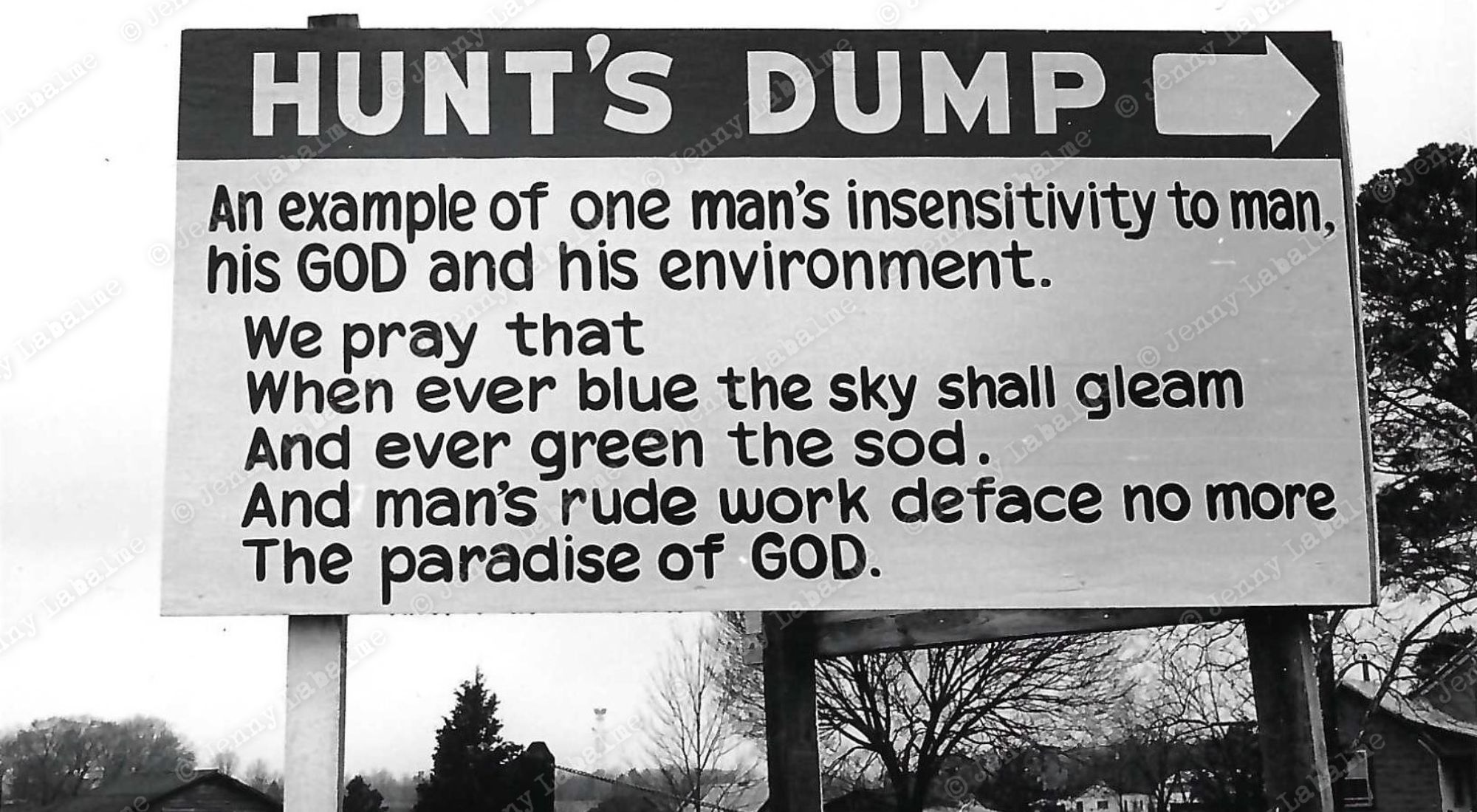

The irony of this sign was not lost on local residents.

“Fired up, ain’t gonna take it no more.”

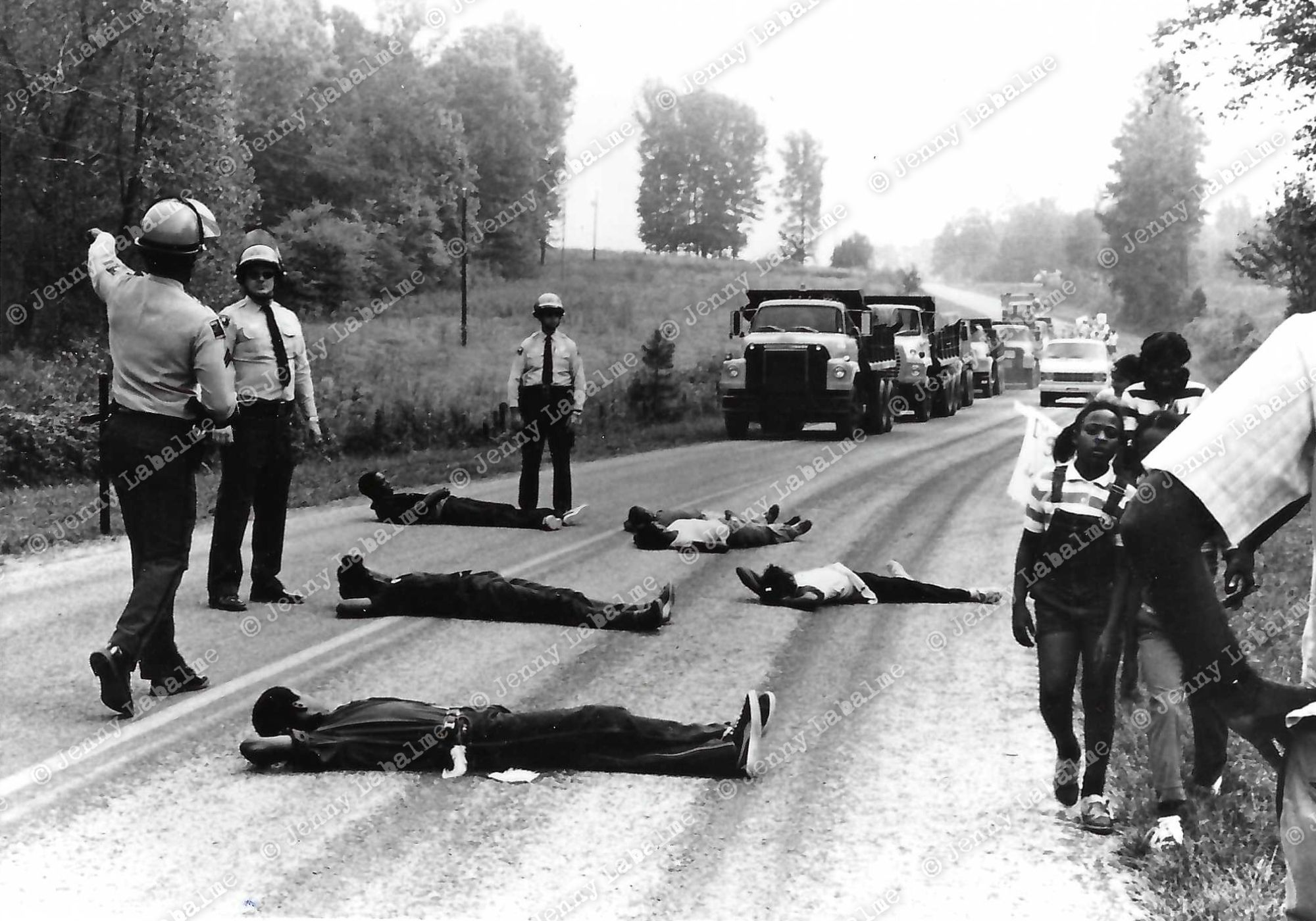

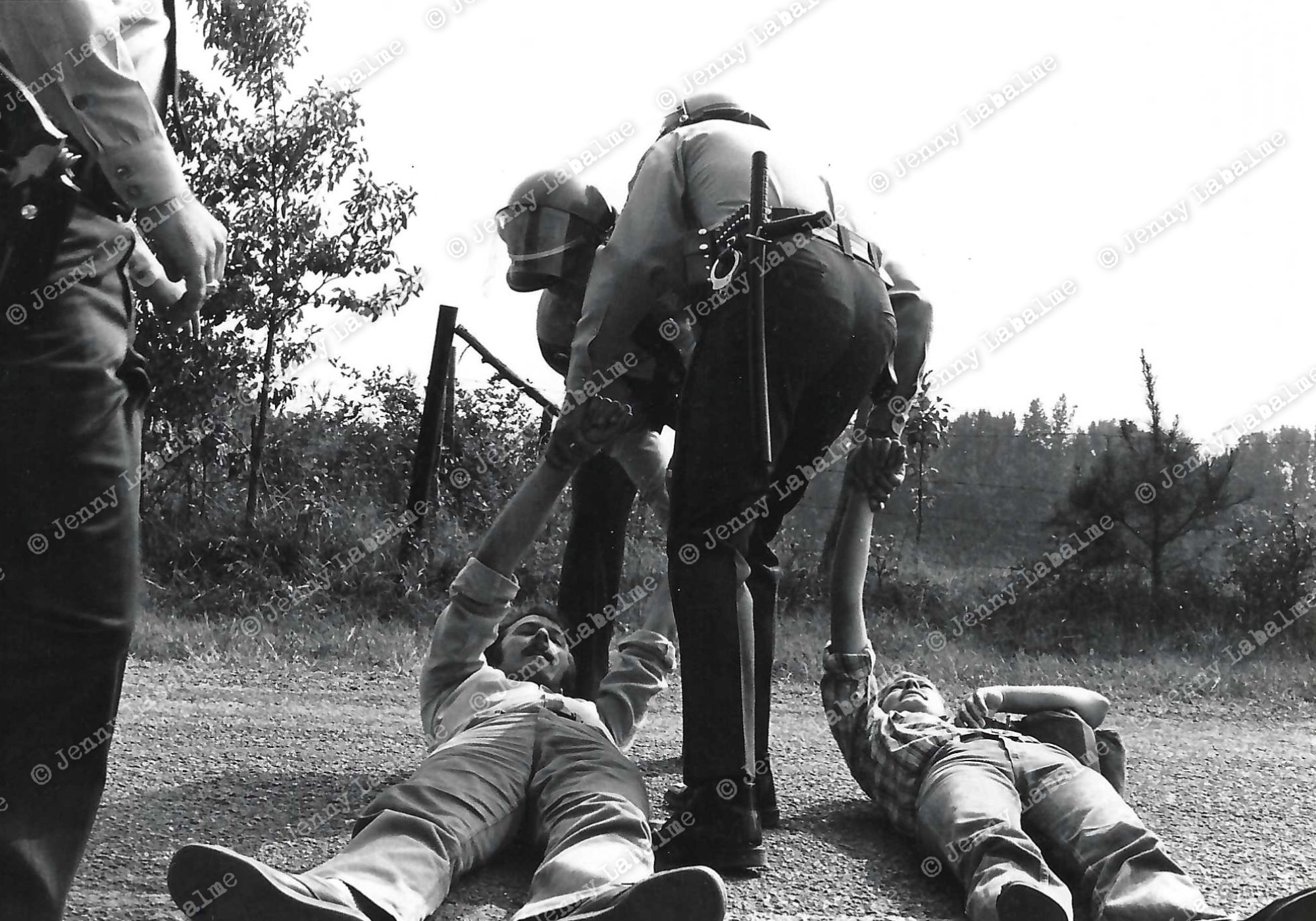

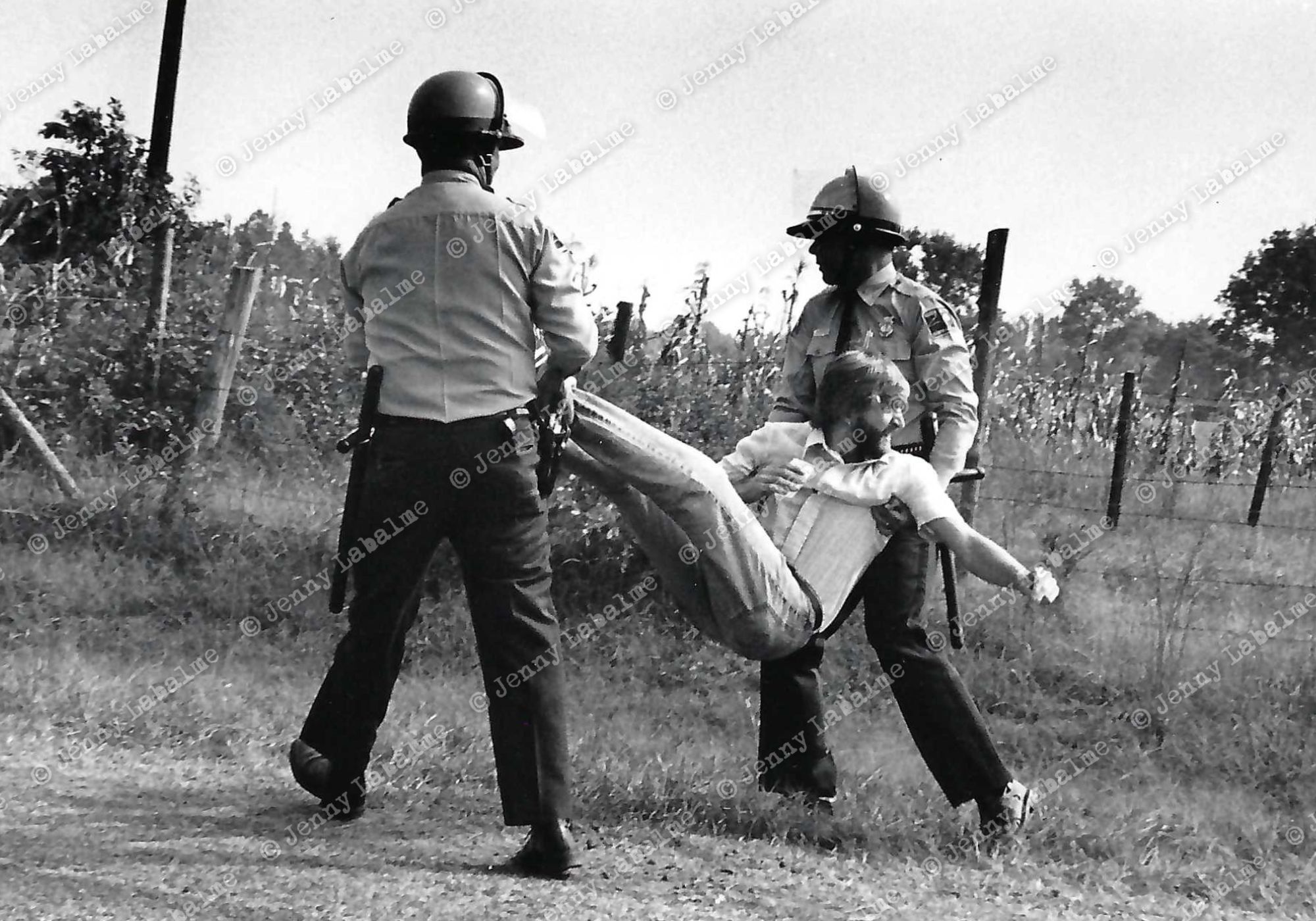

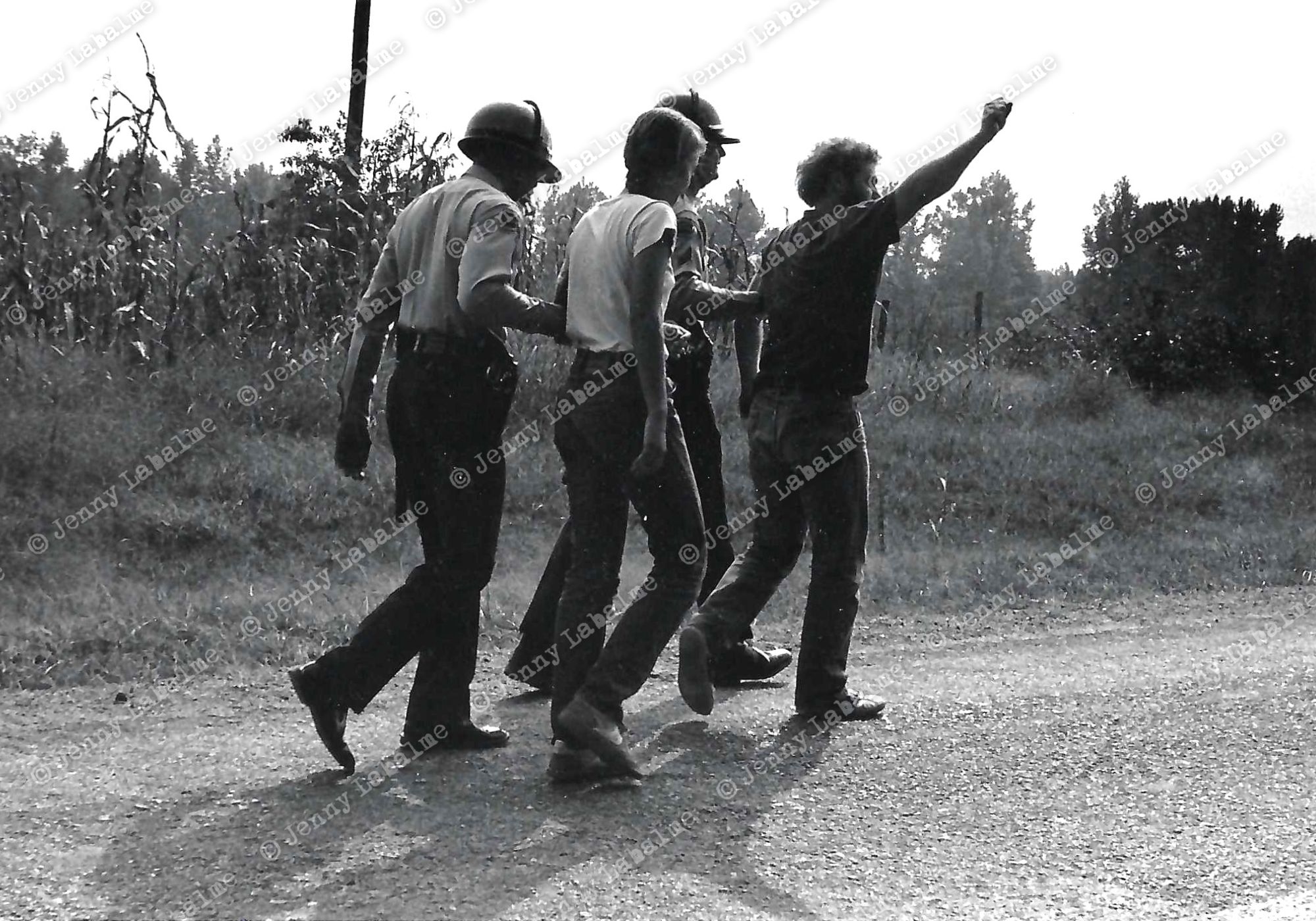

Demonstrators protested every day. The purpose of lying in the road and engaging in civil disobedience was to stop the trucks.

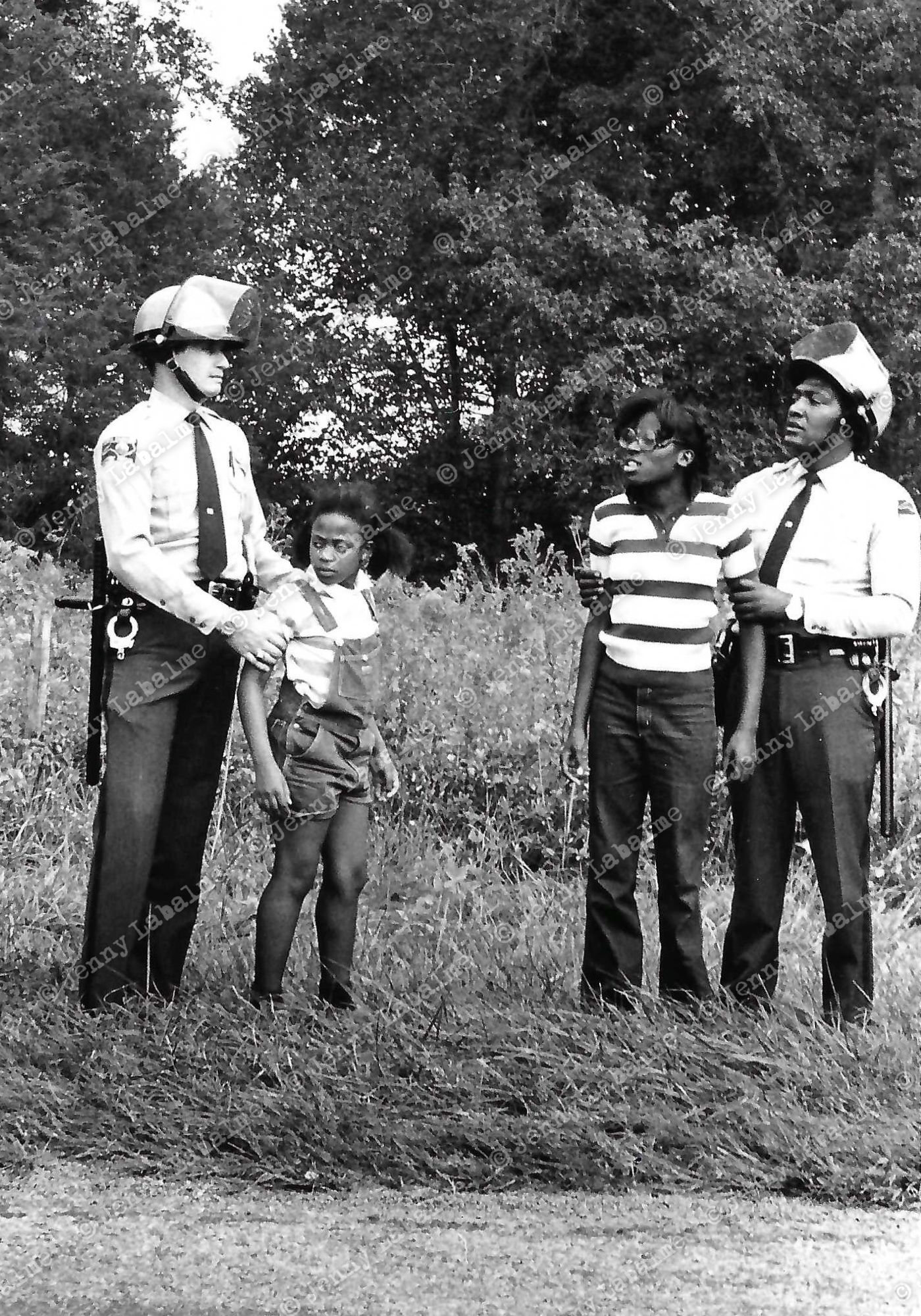

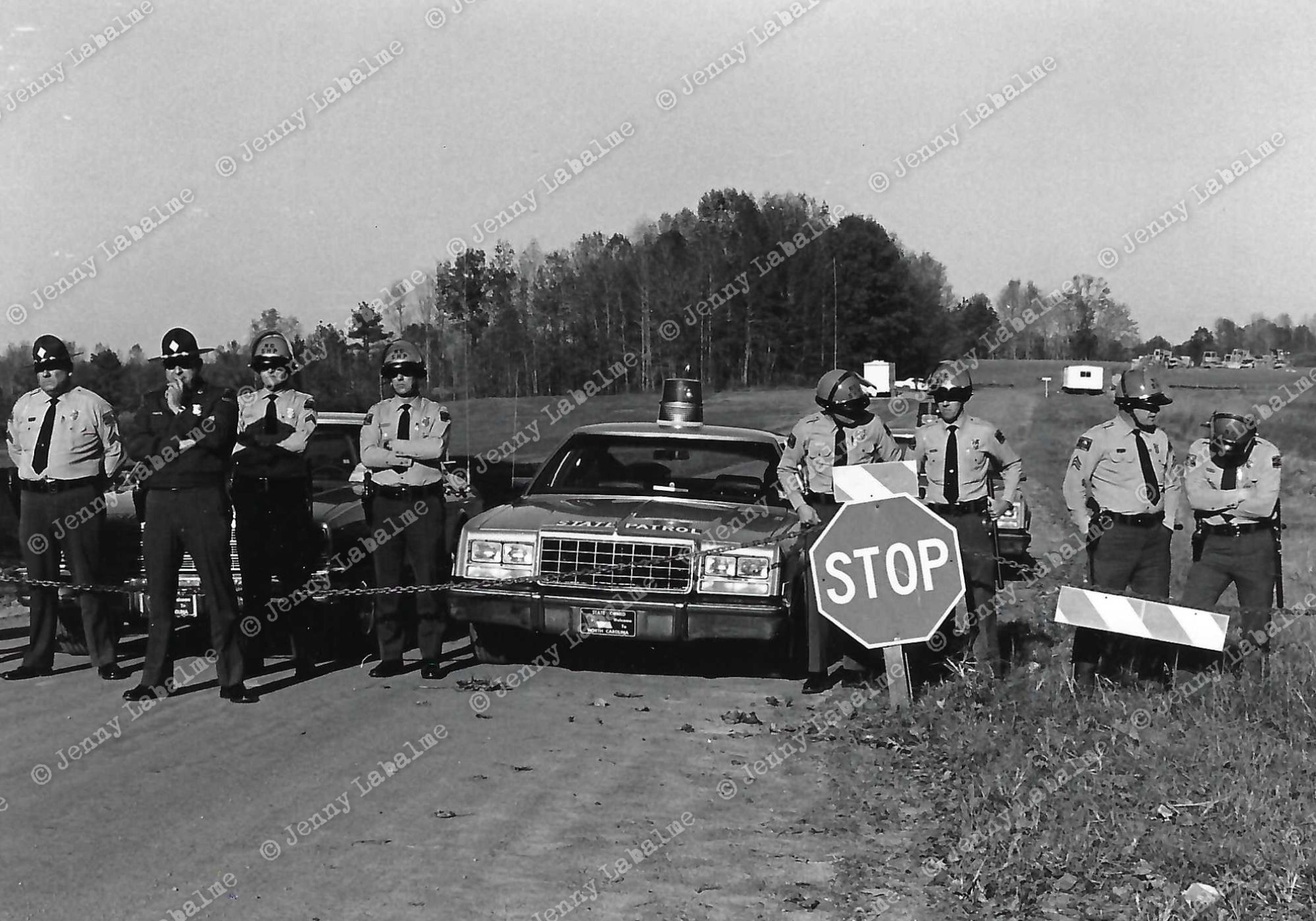

March organizers were committed to keeping the protest non-violent and preventing their demonstrators from being hurt. People were reminded before marching to respect the state police because they were trained to respect and properly treat the protesters.

Local citizens helped out in creative ways if they were unable to march and get arrested.

Wayne Moseley, who was arrested twice, remembered how several local youths devised a way to feed him and others who were held in the jail’s exercise yard.

“They tossed biscuits and chicken over the chain-link fence when they realized we had not eaten,” Moseley recalled.

Moseley’s mother, Ellen Shearin Moseley physically was unable to march, so she doled out apples and water from her car to demonstrators.

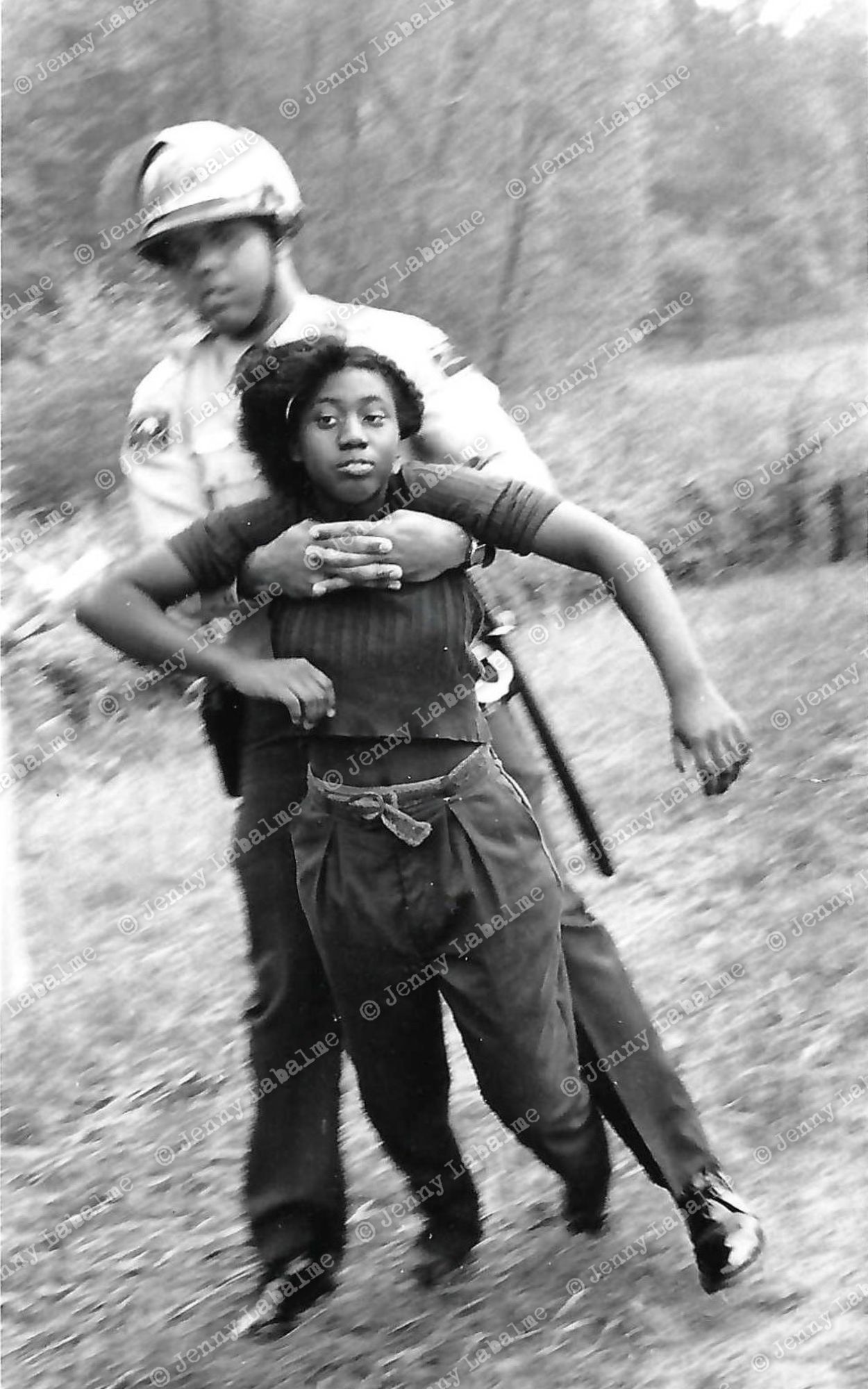

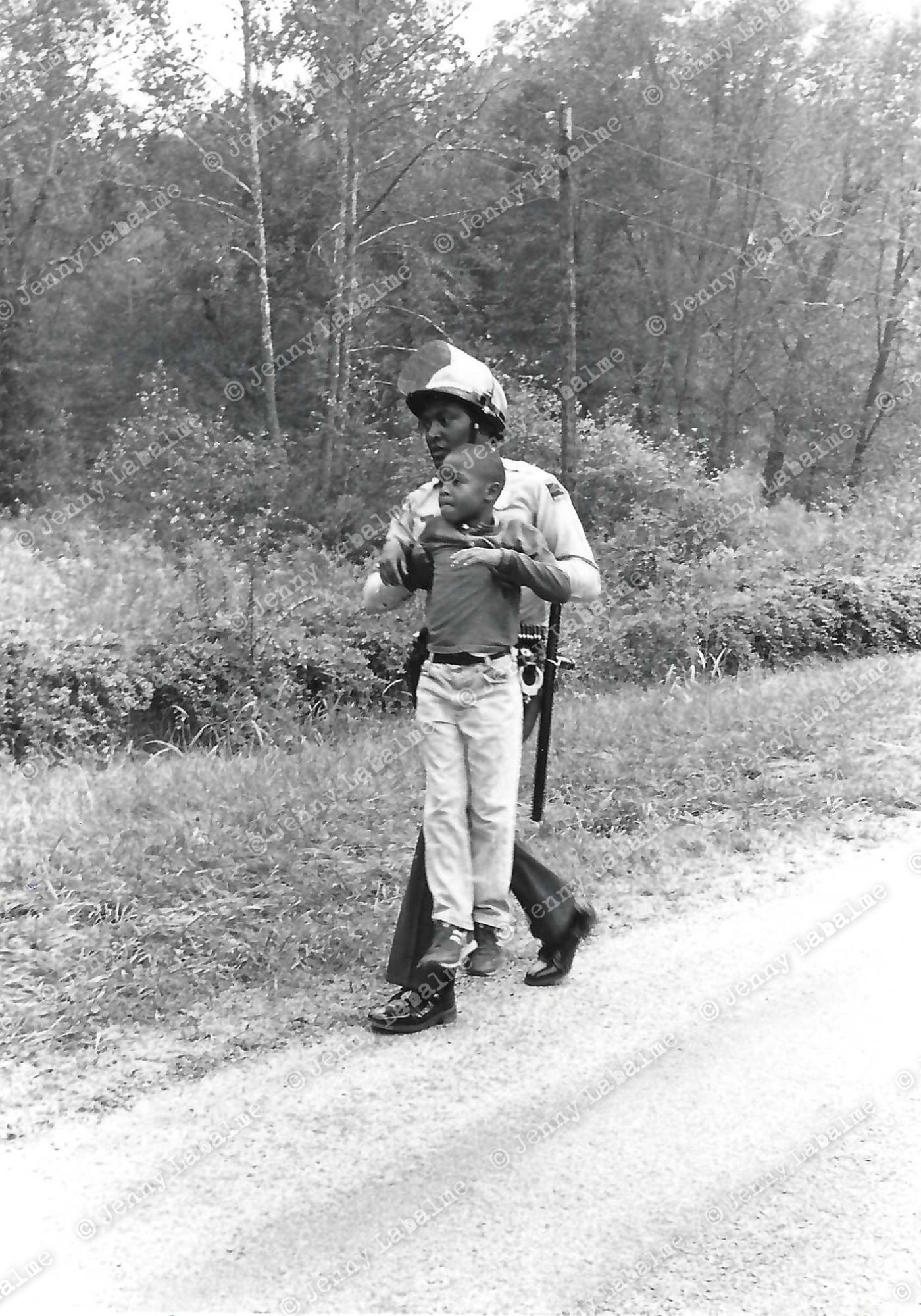

Oct. 4, 1982: Police arrested 39 juveniles and 44 adults.

“I am somebody. I may go to jail. But I am somebody.”

Juveniles were rarely charged with any offense and often released to the custody of their parents. Adults were charged with impeding traffic, a state offense punishable by a maximum sentence of 30 days in jail.

Some offenders were released on their own recognizance. Others had to post a $100 bond. Second and third offenders had to post $500 and $1,000 secured bonds respectively.

Of the 523 hauled to jail, all charges were dropped in district and superior courts.

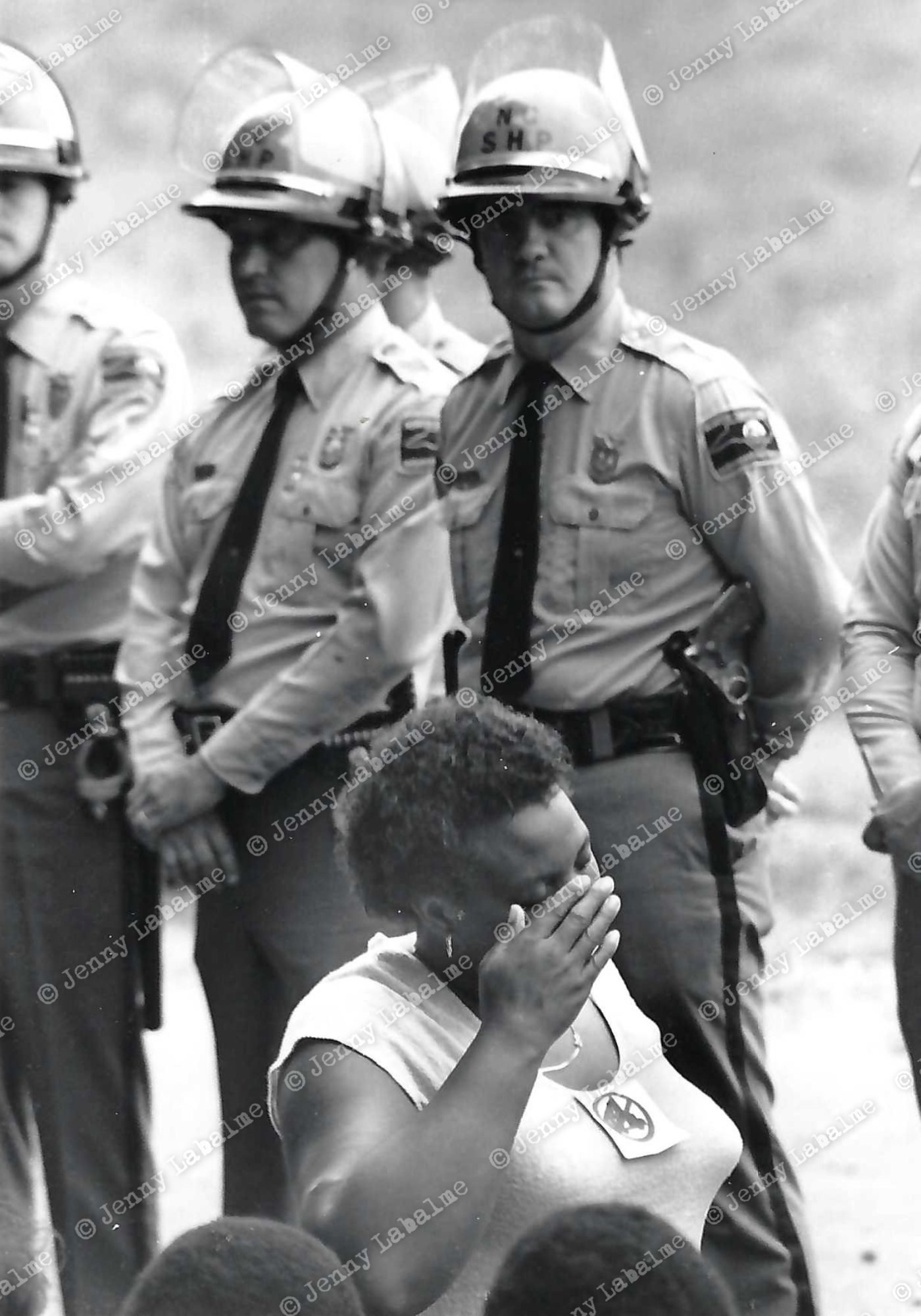

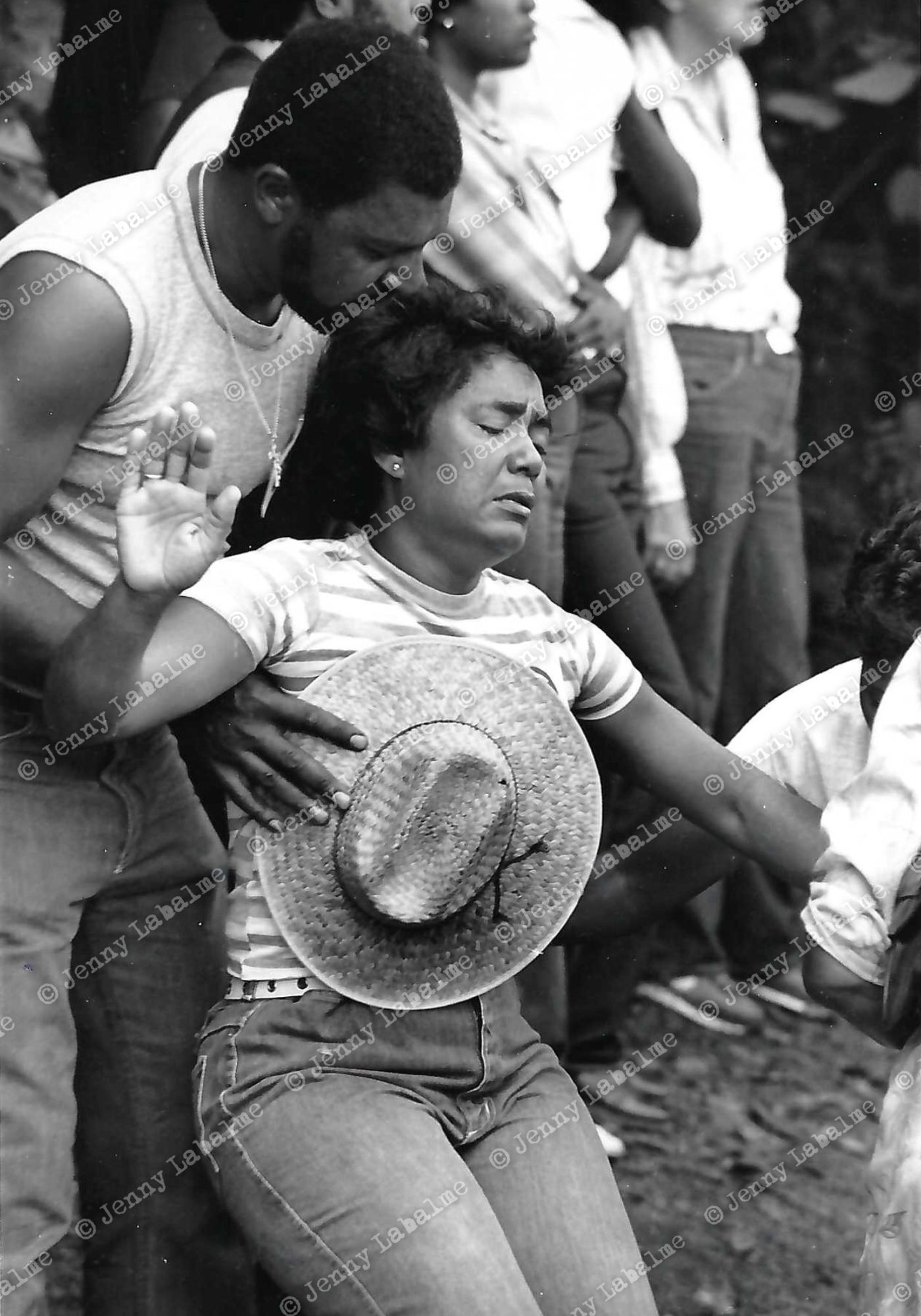

Prayer was an integral part of the protests. People were frightened about going to jail. Before every meeting, church gathering, march and arrest, demonstrators would kneel, bow their heads and pray to God for strength and forgiveness.

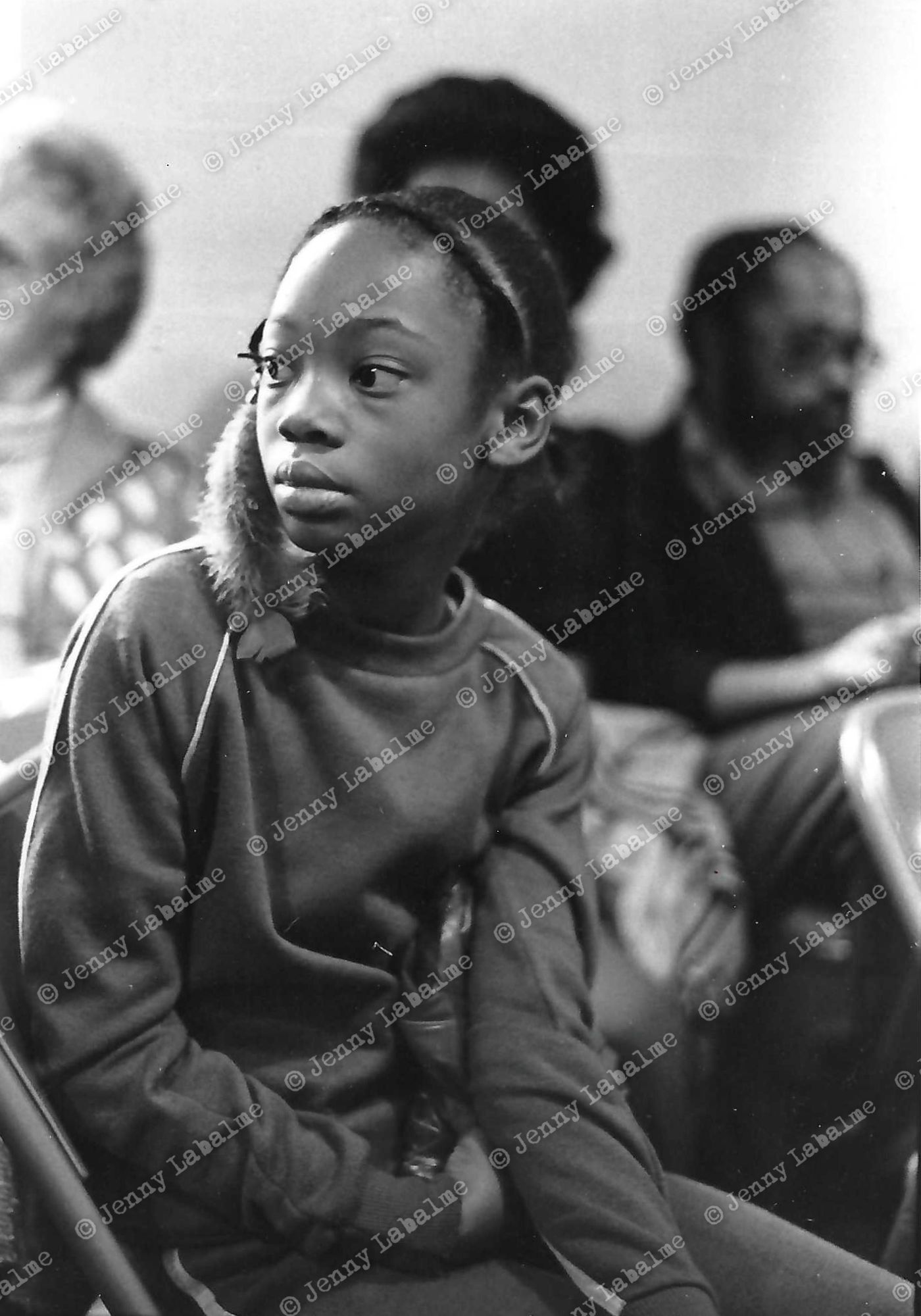

Grassroots Mobilization

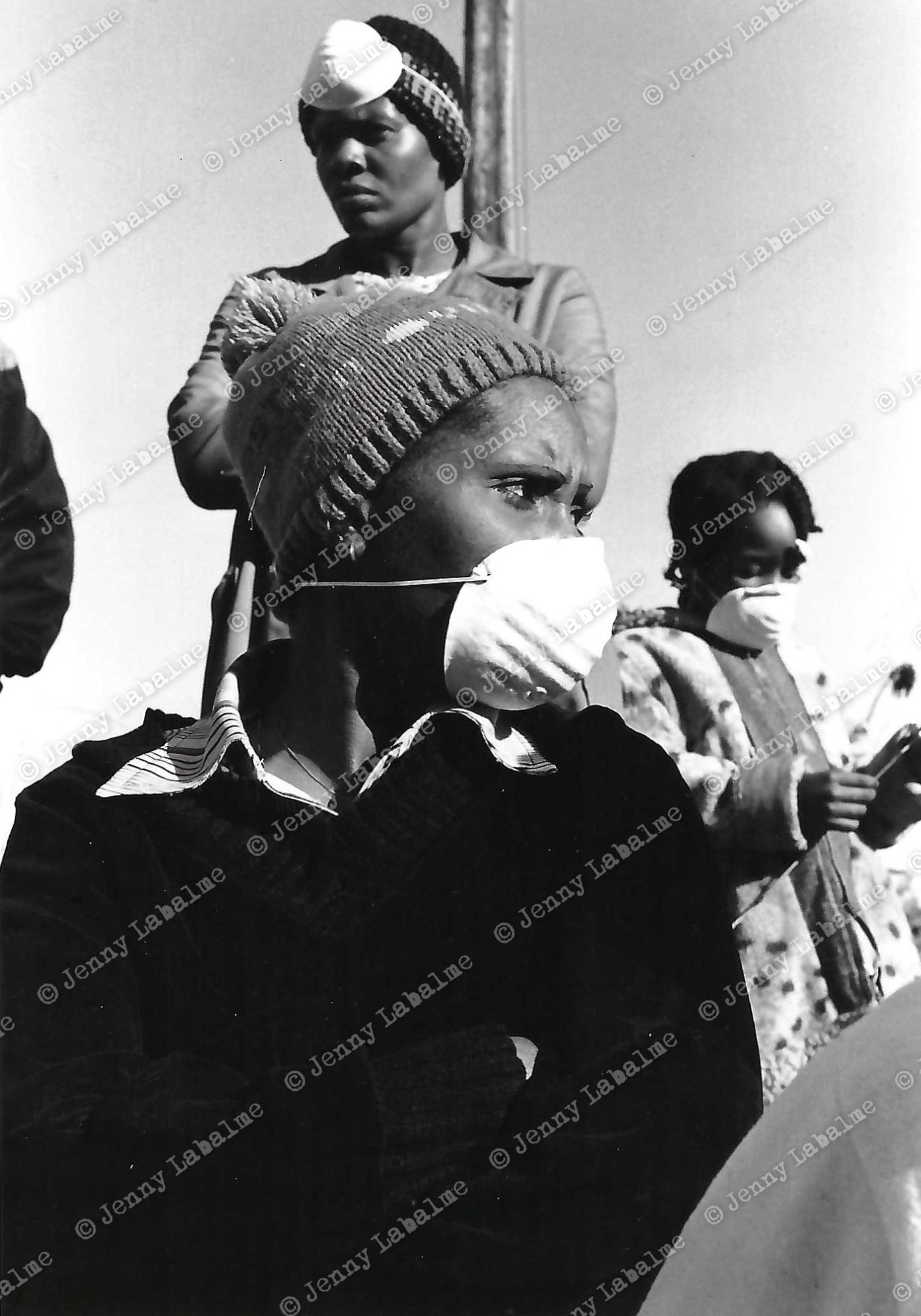

When Dollie Burwell (in photo with mask) was arrested on the first day of the demonstration, her 10-year-old daughter Kim was in tears.

“It worried me because I thought maybe she had just gotten scared of all the police.” said Burwell, who at the time lived three miles from the landfill. “When she saw everybody getting arrested, she knew then that PCB was coming to Warren County … and she thought immediately that everybody would start getting cancer.”

Burwell was 2nd vice president of the Warren County Citizens Concerned About PCB and among one of the most active local citizens.

Throughout the protest, Warren County citizens’ faith and determination were marked by a blend of moral and religious beliefs.

At the time, EPA rules required that landfills be at least 50 feet above groundwater and that sites be located where there were “thick relatively impermeable formations such as large-area clay pans.”

Warren County’s dump met neither of these. The water table was seven feet below the landfill and only small amounts of clay were present in the highly permeable soil. The EPA waived both these regulations to allow North Carolina to approve and construct the site in Warren County.

State officials dismissed residents’ accusations that the landfill’s location was picked for political and racial reasons. Before the protests, a multiracial group of concerned residents met with Gov. James B. Hunt without success.

The Rev. Leon White, field director of the United Church of Christ’s Commission for Racial Justice in Raleigh, N.C.